Immerse yourself in history.

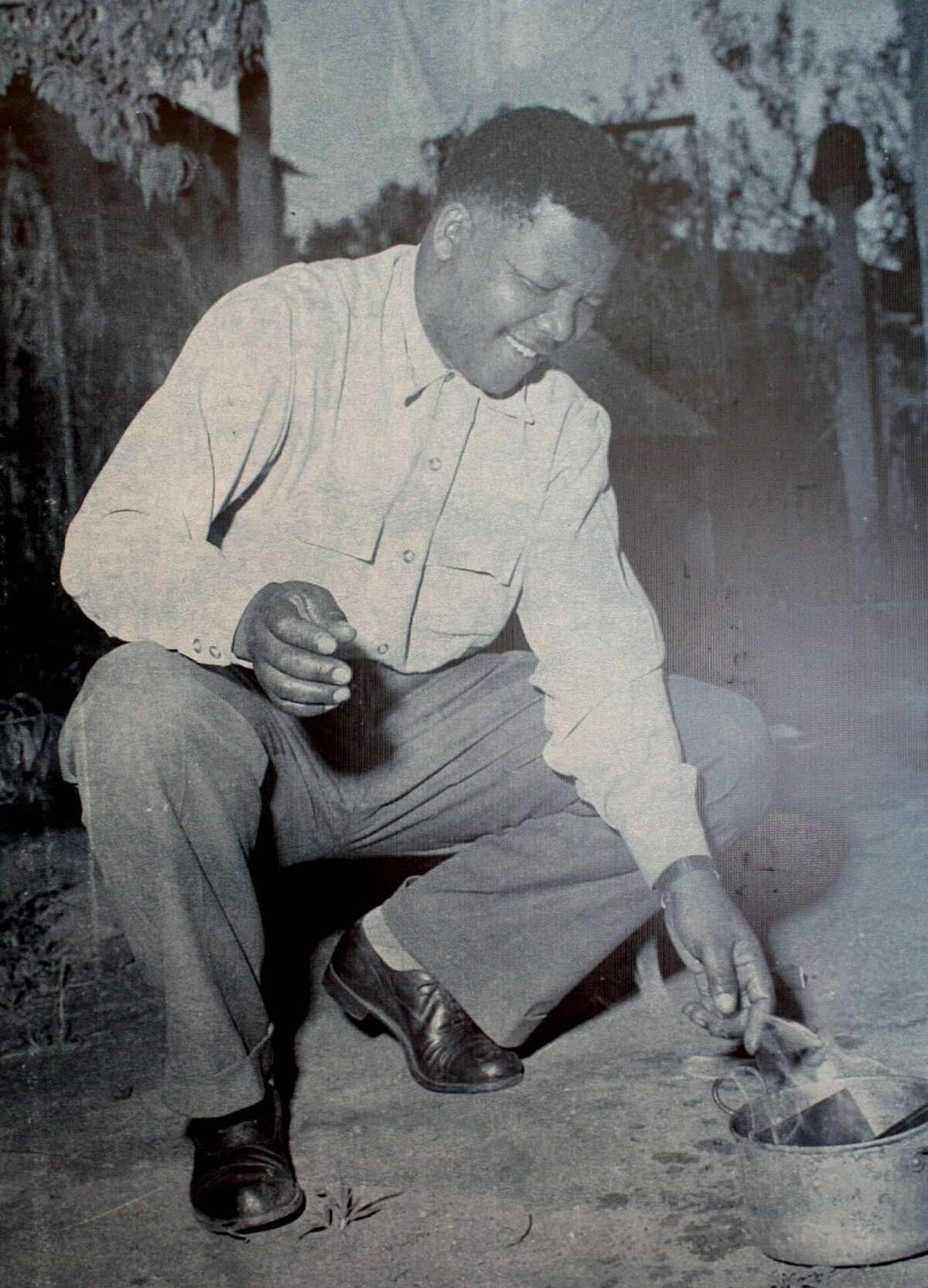

“Education is the most powerful weapon that can be used to change the world. ”

- Nelson Mandela

Please take time reading through this resource. Here you will find a timeline that guides you through South African history and culture. We detailed momentous events, remarkable people, and unjust legislation that deeply impacted the nation.

Though cultural conflict began as far back as the colonial era, a more recent system of injustice known as Apartheid marked the country with ongoing conflict that they continue to recuperate from present-day. We will be exploring South Africa’s history leading up to the Apartheid era and how this system of oppression changed everything.

Click on Titles or Photos to read more…

Let’s start here.

We’re beginning in the 1600s to understand how Southern Africa became a multicultural region, and how that affected the native people.

1652 - The Dutch Arrival

Originally South Africa was inhabited by indigenous San and Khoikhoi people in the South, followed by migrating Bantu speaking people from the North. In 1652, The Dutch East India Company established the first European settlement in southern Africa in Table Bay (Cape Town). Created to supply passing ships with fresh produce, the colony grew rapidly as Dutch farmers settled to grow crops. Shortly after establishing the colony, slaves were imported from East Africa, Madagascar and the East Indies.

“Race is a socially constructed idea. It artificially divides people into groups based on characteristics such as physical appearance. BUT scientifically there is only one race, the human race.”

-Insert Source from Apartheid Museum

Apartheid, which translates from Dutch to “Separateness; Aparthood”, lasted from 1948-1994, was an era that enforced racial separation legislation instituted in favour of the White minority.

148 Laws

Under Apartheid, 148 oppressive laws were enforced to uphold this systematic "aparthood". Click and scroll through the images below to learn about some of these laws that shaped South African history.

1950 - Homelands

One of the Apartheid era government laws, The Group Areas Act, divided cities and towns into segregated residential and business areas and removed thousands of Coloureds, Blacks, and Indians from white occupation areas. Blacks were treated like “tribal” people and were required to live on the reserves under hereditary chiefs except when they worked temporarily in white towns or on white farms. The government began to consolidate the scattered reserves into ten distinct territories, designating them as the Homeland or Bantustan of a specific Black ethnic community.

Whatever a Black person’s culture was, they had to go to the given Homeland. For example, if a Black man or woman was of Zulu origin, they were assigned to go to KwaZulu, the Homeland designated for Zulus. The Apartheid government created ten Homelands in total; two, Ciskei and Transkei for the Xhosa, Bophuthatswana for the Tswana, KwaZulu for the Zulu, Lebowa for the Pedi and Northern Ndebele, Venda for the Vendas, Gazankulu for Shangaan and Tsonga, and Qwa Qwa for the Basothos.

Bantustans, or Homelands, were meant to become independent from South Africa. It was an Apartheid government strategy to push all Blacks out and isolate them from South Africa, consequently denying them protection and any remaining rights they could have in the country. Meaning that Blacks would have to support themselves in these areas, which was impossible because the local Homelands did not have developed economies. They relied almost entirely on White South Africa’s economy. Farming was not very viable because the farmlands were in poor condition due to soil erosion and overgrazing. As a result, millions of Blacks had to leave the homelands daily and work for white farmers, in the mines, or other jobs in the cities. While established to permanently remove the Black population from white South Africa, ironically, the Homelands served as labour reservoirs, housing the unemployed, available whenever white South Africa needed their labour.

1960 - The Sharpeville Massacre

In March 1960, the PAC launched a new anti-pass campaign. Thousands of unarmed Blacks courted arrest by presenting themselves at police stations without passes. At Sharpeville, a Black township near Johannesburg, the police opened fire on the crowd outside a police station. At least 67 Blacks were killed and more than 180 wounded, most of them shot in the back. Thousands of workers then went on strike, and in Cape Town, some 30,000 Blacks marched in a peaceful protest to the centre of the city. Rebellion in rural areas also erupted at this time against the homeland authorities. The government mobilized the army to reestablished control by force, banned the ANC, and arresting more than 11,000 people under emergency regulations.

“During my lifetime, I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

— Nelson Mandela’s now-famous closing words from his speech in the defendant’s dock during the Rivonia Trials

The struggle intensifies

South Africa, increasingly isolated as the last bastion of white racial domination on the continent, became the focus of global condemnation.

At that time, the National Party’s leadership passed to a new class of urban Afrikaners—business leaders and intellectuals who, like their English-speaking white counterparts, believed there needed to be reforms made to appease foreign and domestic critics. Pieter W. Botha became prime minister in August 1978. His government introduced some reforms, repealing the bans on interracial sex and marriage, desegregating many hotels, restaurants, trains, and buses, removing the reservation of skilled jobs for whites, and repealing the pass laws. But it also increased state controls.

The struggle intensified during the early 1980s and became further polarized. A new constitution of 1983 attempted to split the opposition to Apartheid by addressing Indians and Coloureds’ grievances but giving Blacks no political rights except in the homelands. It also vested sweeping powers to an executive president, namely Botha. In response, the United Democratic Front arose. They closely identified with the exiled ANC. Strikes, boycotts, and attacks began escalating, and in 1986 the government declared a nationwide state of emergency and embarked on a campaign to eliminate all opposition. For three years, police and soldiers patrolled the Black townships in armed vehicles. They destroyed Black squatter camps and detained, abused, and killed thousands of Blacks. Rigid censorship laws tried to conceal these actions by banning television, radio, and newspaper coverage.

Long-standing critics such as Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, defied the government and remained actively involved in civil disobedience against the Apartheid regime. During his inaugural sermon as the sixth Bishop of Johannesburg, Tutu declared that he would call on the international community to introduce punitive economic sanctions against South Africa unless Apartheid had not begun to be dismantled within 18 to 24 months.

Hendrik F. Verwoerd played a major part in transforming apartheid from an election slogan into practice…